“Our real journey in life is interior; it is a matter of growth, deepening, and of an ever greater surrender to the creative action of love and grace in our hearts. Never was it more necessary for us to respond to that action.”

In June, I walked 120 miles following the length of the Coa River in central Portugal, from source to mouth, tracking a story about rewilding and the most endangered wildcat on Earth, the Iberian lynx—a story I’ll be updating you all on here soon.

I was proud of myself for having a hyperlight pack to move light and nimble. That was, except for one item:

The 450-page Asia Journal of Thomas Merton.

Something’s been drawing me toward Merton these days.

The Trappist monk, mystic, social activist, and poet was prolific during his life that ended abruptly after getting electrocuted in 1968 when an electric fan fell into his shower in Bangkok. (I call foul play and still keep electronics away from the shower because of this fact.)

My recent spiking interest in Merton, I think, is a function of sitting with how uncomfortable the word God makes me feel, and how I’m trying to slowly, awkwardly nuzzle up to its mouthfeel.

Now, I have no affiliation with organized religion, but have been spiritually curious for most of my life, secretly intrigued by the more subversive of Christian voices who translate Western faith lines in ways that center inclusion, liberation, and environmental justice, who critique the Church not to burn it to the ground but as a way into its essential parts, while devoted fiercely to the galvanizing power of faith and congregation. (Martin Shaw and Paul Kingsnorth come to mind, of course, recently.)

And though I certainly won’t be offering my allegiance to the Christian faith anytime soon, I find myself carrying persistent questions about how faith and God and worship play a role in unraveling times, the rise of neofascism, capitalist desperation, exploding automation, tech escapism.

I see this turn toward the transpersonal as not totally surprising, not some collective delusion but perhaps a growing need of transcending the Self, to discover some renewable and sustaining existential fuel source during times of dislocation and despair, fracture and hyper-individualism.

It’s clear that many are hungry for finding ways toward ecological viability, for finding routes through these capitalist ruins, for grieving what’s already lost and will continue to unravel, and that this will require us to turn toward an authentic frame of inquiry that divests from doppelgänger fracture: Self-as-brand, Self-as-hero, and instead reclaiming a radical divinity in devotion to the feral gods of the living, breathing world.

Thomas Merton: Anarchic Trappist Mystic

Recently, writing mentor and friend David James Duncan recommended I stay away from Merton’s The Seven Storey Mountain and focus on these three texts instead:

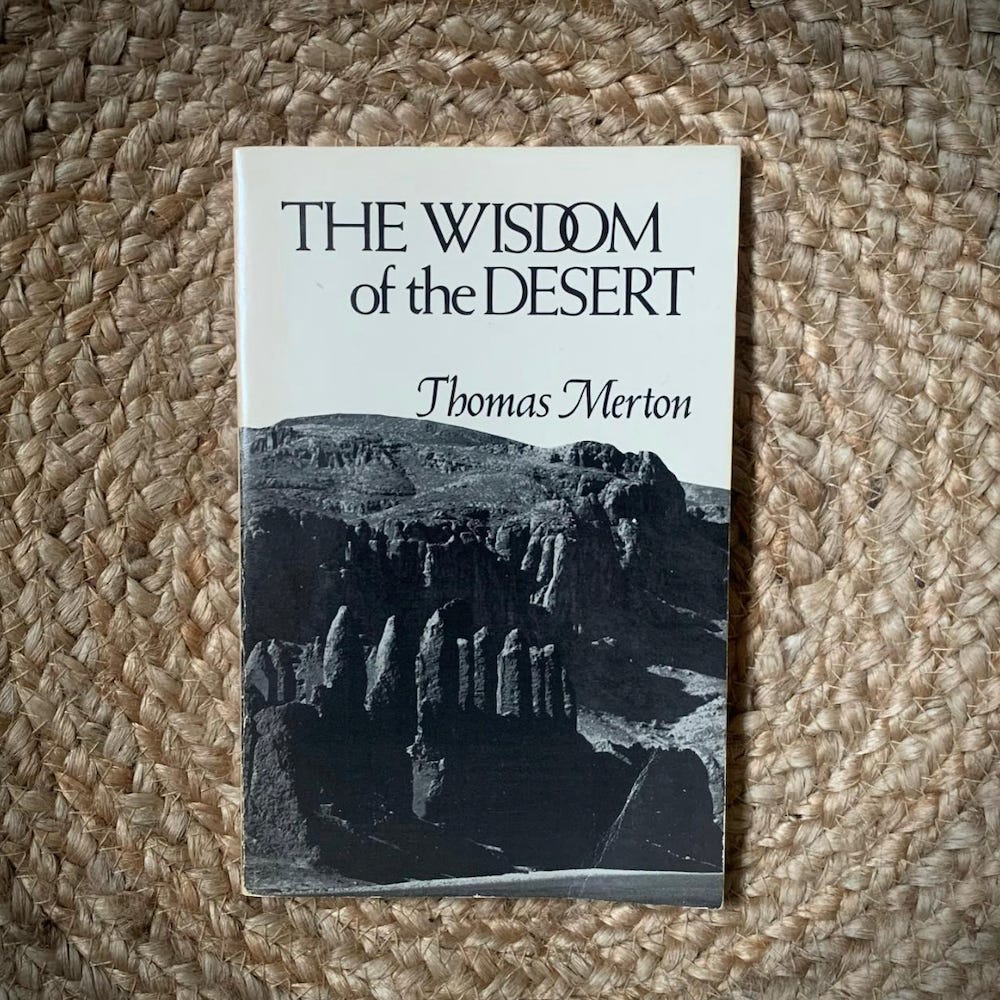

The Wisdom of the Desert

New Seeds of Contemplation

The Asian Journal of Thomas Merton

I thought after spending a ton of time with these texts, it’d be compelling to synthesize central themes that travel through these major works, an attempt to distill some emergent patterns in his work for the uninitiated, a way to increase the resolution on what this mystic was circling around and to try and understand how his wisdom might help us navigate the ecological and existential moment we’re all in right now.

Below you’ll get my Mandorla 200 entry for all three texts (Fact: Thomas Merton and Toni Morrison are the only three-time guests on this book project.)

The Wisdom of the Desert (1960)

(81/200) “What good does the wild hermit serve when the world burns? Perhaps withdrawing into bone-bleached landscapes is peak selfish, but then what if it’s quite the opposite? What if the gulf separating modern me from true me has grown so wide that this pixelated busy chatter grid no longer affords sustained quietude to hear the song of my own divinity? And if we can no longer hear such inner wisdom, preferring instead the pyrotechnics of overcivilized-gossip-compulsive-reactivity, then I am only perpetuating further separation through violent language and action, rarely choosing to look at our Earth-Self from a unified gaze. Temporary retreat—saying nothing, offering no opinion, no posturing, no oxygen taken from another, no colonizing someone else’s attention—becomes then a radical act, resting in the presence of Mystery or God or whatever you call that thing that’s bigger than us, resting in a landscape of old silence. Because beyond convulsing domesticity, one might again start to hear a song in the silence, and that it’s been there all along. We just first had to check our fidelity to noise. We had to simply start listening.”

New Seeds of Contemplation (1961)

(103/200) “This is my false self writing. This is the version of me concerned with being liked, being seen, restless in my smallness to be worthy of your attention. But this is not my true self. No, nested within the billboard self exists an innermost Being, one that both includes and exceeds this version. You might feel this in your bones, too, a humming presence that will outlast your decay. You might call it God; I call it Meadow, a fragrant wholeness winking in quiet moments, shucking the separate me as it tenderly unsnaps mask after mask of social expectation. Because it’s exhausting to worship a false self. What happens if we empty the self and surrender fully to Mystery instead, to an enduring love so countercultural in its dance with the world? This kind of contemplation is spiritual wonder. And if the word God makes you squeamish, stick with Meadow for now, that sun-crisped exhale, a clearing to inhabit our full selves in collision with all the violation and beauty of the world, no longer having to bear it all in that little single-serving Machine body they keep selling us. You are already free. You are the Meadow. I can smell it.”

The Asian Journal of Thomas Merton (1973)

(106/200): “What of all this separateness? Such divine play suggests we are living perfectly-cut individual stories of ego-dance until the grave, but the mystic knows this to be illusion. She sees this as cosmic charades, for true devotion understands phenomena to be unified, and the real work is to unclench our fists from cultures that feast on keeping things Other. The journey to wholeness proves—wait for it—pathless: No endless striving. No constant consuming. Rather, we inhabit a certain grace with the sacred center of things, a grace in trusting what underlies all of this. From Trappist hermitages to Buddhist ascetics, we paradoxically crush this bondage in solitude, breaking matrimony to a never-enoughness that does not find Mystery or God or Whatever in its wholeness. Still, here I am, picking up shiny bits of broken glass and calling it a life. No more. To seek outside oneself is to remain forever hungry, to miss the Truth beating in our blood-rich heart. Yes, this no-path isn’t easy for its main ingredients include radical devotion, loneliness, and surrender, but what world do you wish to inhabit: fractured Self in a fractured world, or whole Self in a whole world?”

Synthesis: Three Major Themes

Simplicity, Solitude, Silence.

How are we to even begin to forge a relationship with the Mystery without incorporating swaths of life that are quiet, alone, and spacious? This is something I’ve been working on in my life: saying “no” more often to things, being discerning about my time and attention, daily meditation and journaling, something I’ve been doing for over two decades. It’s clear that, for Merton, the path toward God, or Mystery or the Universal One, or whatever you care to call this, is a game of subtraction, not addition.

“These Fathers distilled for themselves a very practical and unassuming wisdom that is at once primitive and timeless, and which enables us to reopen the sources that have been polluted or blocked up altogether by the accumulated mental and spiritual refuse of our technological barbarism. Our time is in desperate need of this kind of simplicity. It needs to recapture something of the experience reflected in these lines. The word to emphasize is experience…What good will it do us to know merely that such things were once said? The important thing is that they were lived.” (Wisdom of the Desert Fathers)

“He has advanced beyond all horizons. There are no directions left in which he can travel. This is a country whose center is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere. You do not find it by traveling but by standing still.” (New Seeds)

“Humility contains in itself the answer to all the great problems of the life of the soul. It is the only key to faith, with which the spiritual life begins: for faith and humility are inseparable.” (New Seeds)

“True love requires contact with the truth, and the truth must be found in solitude.” (Asian Journals)(Dis)Identify With Your False Self.

Throughout these three texts, there’s this notion that we all carry around with us this false self, an identity we perform in the world, the ego-self, a branded version that navigates the middle world and reacts and postures. This is a function of a lot of things, but Merton stresses the need to notice and remove our allegiance to this false self in an attempt to know God better, what he calls the True Self. The True Self is in congruence with Mystery, with God, in service to and listening for their invitations and tugs all around us. This has been a task for me. If anything, I’ve recently just become more aware than ever when my false self is in the driver seat, when this false self is being overreactive, inauthentic, people-pleasing, while the True Self always feels more at peace, more attuned and listening, slower and more true. The real journey isn’t external; it’s an interior surrender.

“Our life becomes a series of choices between the fiction of our false self, whom we feed with the illusions of passion and selfish appetite, and our loving consent to the purely gratuitous mercy of God.” (New Seeds)

“What can we gain by sailing to the moon if we are not able to cross the abyss that separates us from ourselves? This is the most important question of all voyages of discovery, and without it all the rest are not only useless but disastrous.” (Wisdom of the Desert)

“The function of faith is not to reduce mystery to rational clarity, but to integrate the unknown and the known together in a living whole, in which we are more and more able to transcend the limitations of our external self.” (New Seeds)

“Everything I think or do enters into the construction of a mandala. It is the balancing of experience over the void, not the censorship of experience. And no duality of experience—void. Experience is full because it is inexhaustible void. It is not mine. It is ‘uninterrupted exchange’. It is dance…. ‘Myself’. No-self. The self is merely a locus in which the dance of the universe is aware of itself as complete from beginning to end—and returning to the void.” (Asian Journals)

“Too much movement. Too much ‘looking for’ something: an answer, a vision, ‘something other.’ And this breeds illusion. Illusion that there is something else.” (Asian Journals)Empty and Be Filled.

This spring I took part in a 10-week online leadership course with Emergence Magazine, and the Diné activist-writer-artist Lyla June Johnston said something that’s stuck with me so palpably. She said that, in Diné, they set in ceremony the intention of becoming a “hollow bone,” to be hollowed out and empty so that the world, Spirit, Mystery, can flute its way through you and you can hear, be moved, and therefore act with the greatest integrity.

Integrity is a word I’m understanding more these days—and I think Thomas and Lyla would both agree—as listening to what your body, the world is trying to share with you, inviting you to follow, and then following with all of your attention and heart. Through these three texts there’s a clear invitation that the way to wholeness is to make space to listen, to not necessarily fill your body with noise and books and podcasts and information and stimulation and arousal, but, rather, to empty and be patient in what the world is intent on filling your cup.

“…the soul is matured only in battles.” (Wisdom of the Desert)

“In order to become myself I must cease to be what I always thought I wanted to be, and in order to find myself I must go out of myself, and in order to live I have to die.” (New Seeds)

“As long as we are on Earth, the love that unites us will bring us suffering by our very contact with one another, because this love is the resetting of a Body of broken bones.” (New Seeds)

Walk Deeper:

READ: Richard Rohr on Merton’s Love of Nature and the Lynn Scabo’s Mystical Ecology of Thomas Merton’s Poetics.

FOLLOW: The Mandorla 200

Thank you for this. I’ve just been recommended Merton by a friend whose faith I trust. Your lay of the land has given me lots of room to stay my own reading of Merton. I feel moved. In appreciation,