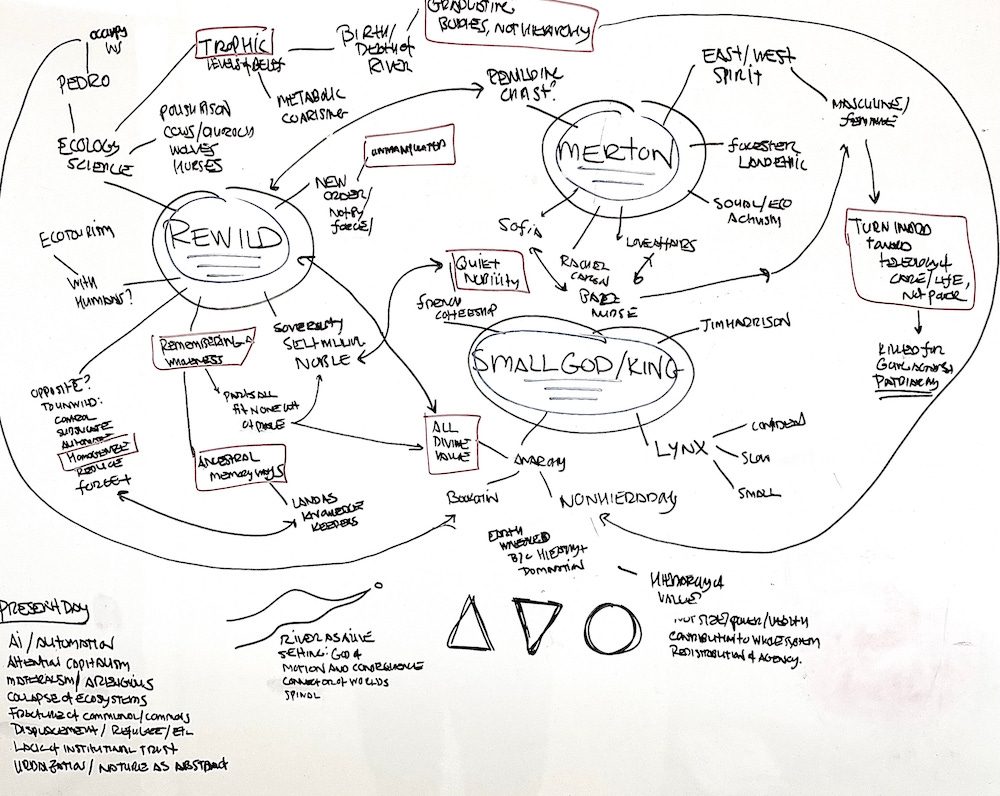

The Iberian Lynx and a Rewilding of an Anarchist Mystic

Extra nutrition from a recent feature published in Emergence Magazine.

Portugal’s River Côa suggested my attendance in 2017.

It took over seven years to heed the call.

For the better half of a decade, I’d grown fixated on one of Europe’s most promising rewilding projects along the 84-mile Côa River in central Portugal. I’m not sure exactly why, but I knew I was curious what rewilding was all about, specifically, what it looked like on the ground to coax one of the world’s most endangered wildcats, the Iberian lynx, back into Portugal.

Last May, I found myself standing at the headwaters of the Côa, to follow the river over five days to the confluence with the Douro, to see what I might find.

What unfolded was so much more complicated and surprising than I could have ever expected.

This week, Emergence Magazine published my story about the immersion, “A Small King: A Mystical Rewilding Along Portugal’s Rio Côa.”

(I’d participated in their online leadership course, Seeds of Radical Renewal, last year, which I can’t recommend enough.)

I’m so excited to share this story with you. It really did feel like something shifted within me, in my process as both a writer and artist, along this river.

Something entered a different chamber in the way I approach storytelling, or, as a recent conversation in Portland, Oregon, with filmmaker Olivia Leigh Nowak suggested, “story facilitation,” that some stories aren’t simply for us to “tell,” that perhaps we might instead “facilitate,” listening long enough with patience to what the land, the residents, the wind, the water, the singing frog has to say, our body porous to the larger animate Body for possible transmission, tuning to what Robert Macfarlane calls “the ecology of selves,” in his forthcoming book.

Instead of storyteller Nick arriving for duty, here to spin a clever yard with a parachute and the ingenuity of one, this experience in Portugal might have been my first body-blurring experience of being radically coauthored by a place, where I wasn’t a sole writer witnessing and recording, but was being actively written, shaped by surprise and surrender.

I know. This might sound squishy to you. But I mean it literally and ferociously.

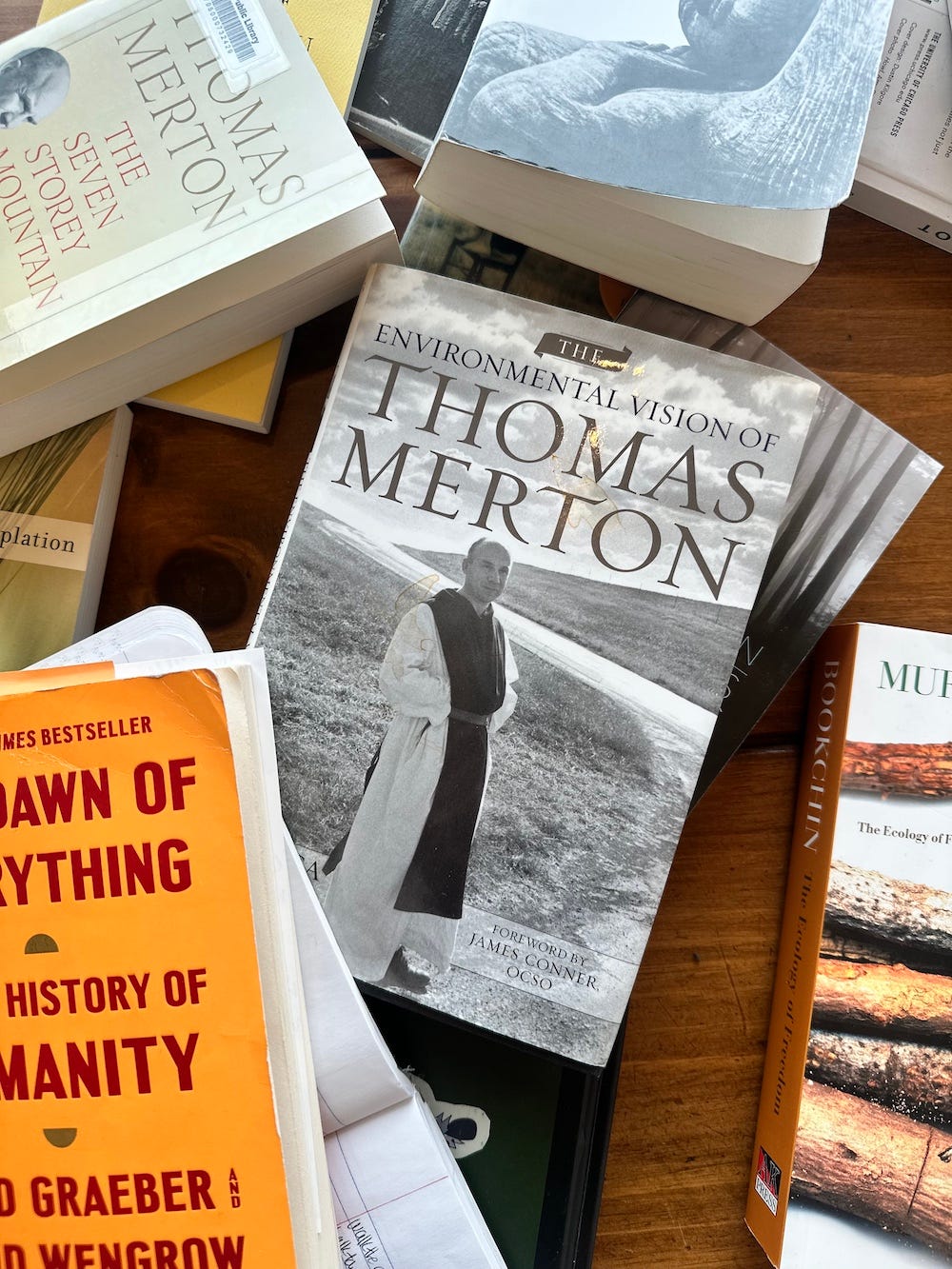

In addition to being shaped by the river, I was simultaneously being tenderized by a wisdom text carried with me along the walk, words from the final days of anarchist-mystic Thomas Merton, which corresponded with a larger self-inquiry about God, divinity, and the natural world:

“My obsession with Merton reflected a growing tension with how uncomfortable the word ‘God’ made me feel and simultaneously how necessary it felt for me to somehow know God better during these destabilizing times. The modern-liberal inheritor of a congenital familial allergy to organized religion, I lugged around a closeted thirst for spirit, cosplaying as a Buddhist for years but secretly courting Christian voices who were pro-liberation and anti-capitalist, who centered justice and contemplation, who critiqued the Church’s shadow of empire—Meister Eckhart, Simon Weil, Richard Rohr, Thomas Merton—those intent not to burn the establishment to the ground but to salvage its essential parts. What I think I desired most was a source of renewable divinity that could orient me to the day’s polycrisis of dislocation and despair, runaway automation and climate spiral, a cultural hyperworship of the self. And this was how Merton remained in my pack: a crude but unavoidable curiosity for the unknowable.”

This is actually the third story I’ve written where a single book became a gravitational force of the narrative:

“Agony and Endurance” (The Dark Mountain Project) was guided by Robinson Jeffers’s Not Man Apart.

“Tamalpais.” Part Two of my forthcoming book uses Snyder’s Mountains and Rivers Without End as a map.

Along the way, the river whispered a few things.

The river uncovered the dangers of hierarchy of value within a landscape, how our political, social, and economic hierarchies can insidiously persist among all domains, including conservation and restoration work.

In the story, something about small kings and small gods emerged, too, that to see the living world and its wildness not only in individual species, but in their tangle of relationships, to see what might call sacred as the very dialoguing in-between itself, not only harbored in a singular sexy figure:

“[Merton’s] words remind me of what seems to be at the very heart of rewilding. Not charismatic leaders with consolidated power, acting unilaterally, but small nobility, small gods at every scale within a landscape—like the Iberian lynx, sometimes referred to as a pequeno rei, or small king: fierce nobility, loyal to its homeland, what poet Gary Snyder once called the ‘ghost wilderness,’ divinity living in the marbled in-between.”

By the fifth day, I would suffer from dehydration and would come down with some of the worst food poisoning of my life—not included in the final essay; you’re welcome!—but I can say, after reading (and listening to it) that this was one of the most meaningful experiences of my life, one that has already planted seeds for future inquiry, future writing, future co-authorship with some wild divinity.

“These small gods surprised me at every turn: God as albino orchid. God as shepherd day-drinker in the middle of the path. God as pancetta offered to a wanderer at dusk. God as black-ink ear tips of a fox. God as wild boar snarl. God as a godless, post-modern skeptic trying to say ‘God’ without apology.”

Go Deeper: Additional Reading

Here’s an incomplete list of some of the central texts and thinkers referenced directly or indirectly in the piece:

Thomas Merton: Asian Journals, New Seeds of Contemplation, The Wisdom of the Desert, Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander. These were the central works I focused on for this piece, as well as the collections, The Environmental Vision of Thomas Merton and When the Trees Say Nothing.

Murray Bookchin: The Ecology of Freedom. A seminal text that helped me think about ecological anarchy and the structures of hierarchy and domination as they relate to political agency.

Fernando Pessoa: The Book of Disquiet, and his short story, “The Anarchist Banker.” One of Portugal’s finest (and weirdest) novelists.

Toni Morrison: A portion of this quote was the North Star for the whole piece, from a talk she gave at the New York Public Library in 1986:

“All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was. Writers are like that: remembering where we were, that valley we ran through, what the banks were like, the light that was there and the route back to our original place.”Dorothy Day: Though her story didn’t make it in the final piece, I was tipped onto her work by a fellow Substacker and former student and have since been learning a ton about the badass Catholic anarchist. This podcast episode was a nice onramp, and on my short list is The World Will Be Saved By Beauty.

George Monbiot: Feral: Rewilding the Land, the Sea, and Human Life.

Rewilding Portugal: Featured in the BBC (1), BBC (2), and the Guardian. Huge thanks to Pedro Prata and his team for their overwhelming generosity of time and direction. These guys are the real deal. Deep inspiration.

Robert Macfarlane: Is a River Alive? Huge guidance from this forthcoming masterclass on narrative nonfiction. I received an advanced copy after writing a first draft and couldn’t believe the shared dialogue between them.

David Graeber and David Wengrow: The Dawn of Everything. The book made my head spin, but also genius and spellbinding and required reading.